Intro

Aphorisms and axioms are powerful tools for self-reflection and understanding the world around us. These timeless phrases capture essential truths and offer insights into the human experience. In this blog post, we've compiled a list of our favorite aphorisms and axioms that will inspire you to think deeply and gain a new perspective on life. Read on for a dose of wisdom and inspiration.

1% Rule

- In Internet culture, the 1% rule is a rule of thumb pertaining to participation in an internet community, stating that only 1% of the users of a website actively create new content, while the other 99% of the participants only lurk. Variants include the 1–9–90 rule (sometimes 90–9–1 principle or the 89:10:1 ratio),[1] which states that in a collaborative website such as a wiki, 90% of the participants of a community only view content, 9% of the participants edit content, and 1% of the participants actively create new content.

90/90 rule

- In computer programming and software engineering, the ninety-ninety rule is a humorous aphorism that states:

- The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time.

Abilene paradox

- A group of people collectively decide on a course of action that is counter to the preferences of many or all of the individuals in the group.[1][2] It involves a common breakdown of group communication in which each member mistakenly believes that their own preferences are counter to the group's and, therefore, does not raise objections. A common phrase relating to the Abilene paradox is a desire not to "rock the boat". This differs from groupthink in that the Abilene paradox is characterized by an inability to manage agreement.[3]

- The term was introduced by management expert Jerry B. Harvey in his 1974 article "The Abilene Paradox: The Management of Agreement".[3] The name of the phenomenon comes from an anecdote that Harvey uses in the article to elucidate the paradox:

- On a hot afternoon visiting in Coleman, Texas, the family is comfortably playing dominoes on a porch, until the father-in-law suggests that they take a trip to Abilene [53 miles (85 km) north] for dinner. The wife says, "Sounds like a great idea." The husband, despite having reservations because the drive is long and hot, thinks that his preferences must be out-of-step with the group and says, "Sounds good to me. I just hope your mother wants to go." The mother-in-law then says, "Of course I want to go. I haven't been to Abilene in a long time."The drive is hot, dusty, and long. When they arrive at the cafeteria, the food is as bad as the drive. They arrive back home four hours later, exhausted. One of them dishonestly says, "It was a great trip, wasn't it?" The mother-in-law says that, actually, she would rather have stayed home, but went along since the other three were so enthusiastic. The husband says, "I wasn't delighted to be doing what we were doing. I only went to satisfy the rest of you." The wife says, "I just went along to keep you happy. I would have had to be crazy to want to go out in the heat like that." The father-in-law then says that he only suggested it because he thought the others might be bored.

- The group sits back, perplexed that they together decided to take a trip which none of them wanted. They each would have preferred to sit comfortably, but did not admit to it when they still had time to enjoy the afternoon.

Amara's law

- states that, "We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run." Named after Roy Amara (1925–2007).

Animistic Fallacy

- The animistic fallacy is the informal fallacy of arguing that an event or situation necessarily arose because someone intentionally acted to cause it.[1] While it could be that someone set out to effect a specific goal, the fallacy appears in an argument that states this must be the case.[1] The name of the fallacy comes from the animistic belief that changes in the physical world are the work of conscious spirits.

Appeal to Flattery

- Appeal to flattery[1] is a fallacy in which a person uses flattery, excessive compliments, in an attempt to appeal to their audience's vanity to win support for their side.[2] It is also known as apple polishing, wheel greasing, brown nosing, appeal to pride, appeal to vanity or argumentum ad superbiam.[3] The appeal to flattery is a specific kind of appeal to emotion.[4]

- "Surely a man as smart as you can see this is a brilliant proposal." (failing to accept the proposal is a tacit admission of stupidity)

- "Is there a strong man here who could carry this for me?" (a failure to demonstrate physical strength implies weakness)

- "You are a stunningly beautiful girl – you should become a model."

Appeal to motive

- A pattern of argument which consists in challenging a thesis by calling into question the motives of its proposer. It can be considered as a special case of the ad hominem circumstantialargument. As such, this type of argument may be an informal fallacy.

Appeal to Nature

- An appeal to nature is an argument or rhetorical tactic in which it is proposed that "a thing is good because it is 'natural', or bad because it is 'unnatural'".[1] It is generally considered to be a bad argument because the implicit (unstated) primary premise "What is natural is good" is typically irrelevant, having no cogent meaning in practice, or is an opinion instead of a fact. In some philosophical frameworks where natural and good are clearly defined within a specific context, the appeal to nature might be valid and cogent.

- That which is natural, is good.

- N is natural.

- Therefore, N is good or right.

- That which is unnatural, is bad or wrong.

- U is unnatural.

- Therefore, U is bad or wrong.[2]

Appeal to novelty

- "If you want to lose weight, your best bet is to follow the latest diet."

- "The department will become more profitable because it has been reorganized."

- "Upgrading all your software to the most recent versions will make your system more reliable."

- "Things are bad with party A in charge, thus party B will bring an improvement if they're elected."

- "If you want to make friends, you have to wear the latest fashion and the trendiest gadgets."

- "Do X because it is Current Year."

Appeal to Motive

- Appeal to motive is a pattern of argument which consists in challenging a thesis by calling into question the motives of its proposer. It can be considered as a special case of the ad hominem circumstantial argument. As such, this type of argument may be an informal fallacy.

- "That website recommended ACME's widget over Megacorp's widget. But the website also displays ACME advertising on their site, so they were probably biased in their review." The thesis in this case is the website's evaluation of the relative merits of the two products.

- "The referee is a New York City native, so his refereeing was obviously biased towards New York teams." In this case, the thesis consists of the referee's rulings.

- "My opponent argues on and on in favor of allowing that mall to be built in the center of town. What he won't tell you is that his daughter and her friends plan to shop there once it's open."

Appeal to Pity

- "You must have graded my exam incorrectly. I studied very hard for weeks specifically because I knew my career depended on getting a good grade. If you give me a failing grade I'm ruined!"

- "Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, look at this miserable man, in a wheelchair, unable to use his legs. Could such a man really be guilty of embezzlement?"

- "Think of the children."

- "You must believe in Jesus because he died for your sins."

Appeal to Poverty

- Argumentum ad lazarum or appeal to poverty is the informal fallacy of thinking a conclusion is correct solely because the speaker is poor, or it is incorrect because the speaker is rich. It is named after Lazarus, a beggar in a New Testament parable who receives his reward in the afterlife.

- Family farms are struggling to get by so when they say we need to protect them, they must be on to something.

- The homeless tell us it's hard to find housing. Thus it must be.

- The monks have forsworn all material possessions. They must have achieved enlightenment.

- All you need to know about the civil war in that country is that the rebels live in mud huts, while the general who sends troops against them sits in a luxurious, air-conditioned office.

Appeal to Wealth

- An argumentum ad crumenam argument, also known as an argument to the purse, is the informal fallacy of concluding that a statement is correct because the speaker is rich (or that a statement is incorrect because the speaker is poor).

- If you're so smart, why aren't you rich?

- This new law is a good idea. Most of the people against it are riff-raff who make less than $20,000 a year.

- Warren Buffett is hosting a seminar. This seminar is better than others, because Warren Buffett is richer than most people.

Appeal to consequences

- Positive form

- If P, then Q will occur.

- Q is desirable.

- Therefore, P is true.

- Negative form

- If P, then Q will occur.

- Q is undesirable.

- Therefore, P is false.

Appeal to accomplishment

- an assertion is deemed true or false based on the accomplishments of the proposer.[77] This may often also have elements of appeal to emotion (see below).

- "How dare you criticize the prime minister? What do you know about running an entire country?"

- "I'll take your opinions on music seriously when you've released a record that went platinum."

- "Get back to me when you've built up a multi-billion dollar empire of your own. Until then, shut up."

- "If you think you know so much about making a video game, make one yourself!"

Appeal to the Stone

- Argumentum ad lapidem (English: "appeal to the stone") is a logical fallacy that consists in dismissing a statement as absurd without giving proof of its absurdity.[1][2][3]

- Speaker A: Infectious diseases are caused by microbes.

- Speaker B: What a ridiculous idea!

- Speaker A: How so?

- Speaker B: It's obviously ridiculous.

Appeal to spite

- An appeal to spite (Latin: argumentum ad odium)[1] is a fallacy in which someone attempts to win favor for an argument by exploiting existing feelings of bitterness, spite, or schadenfreude in the opposing party. It is an attempt to sway the audience emotionally by associating a hate-figure with opposition to the speaker's argument.

- Why shouldn't prisoners do hard labor? The places are full of scumbags!

- Stop that recycling! Aren't we tired of Hollywood celebrities preaching about saving the Earth?

- Why should they even have more? I got nothing from the state and look at what I had to give off to pay for my own studies!

- Not the opera, Hitler loved that, let's go to the circus instead.

Argument to moderation

- Argument to moderation (Latin: argumentum ad temperantiam)—also known as false equivalence, false compromise, [argument from] middle ground, equidistance fallacy, and the golden mean fallacy[1]—is an informal fallacy which asserts that the truth must be found as a compromise between two opposite positions.[2][3] An example of a fallacious use of the argument to moderation would be to regard two opposed arguments—one person saying that the sky is blue, while another claims that the sky is in fact yellow—and conclude that the truth is that the sky is green.[4] While green is the colour created by combining blue and yellow, therefore being a compromise between the two positions—the sky is obviously not green, demonstrating that taking the middle ground of two positions does not always lead to the truth.

Attribution (Psychology)

- Humans are motivated to assign causes to their actions and behaviors.[1] In social psychology, attribution is the process by which individuals explain the causes of behavior and events. Models to explain this process are called attribution theory.[2] Psychological research into attribution began with the work of Fritz Heider in the early 20th century, and the theory was further advanced by Harold Kelley and Bernard Weiner.

Argumentum ad populum

- In argumentation theory, an argumentum ad populum (Latin for "argument to the people") is a fallacious argument that concludes that a proposition must be true because many or most people believe it, often concisely encapsulated as: "If many believe so, it is so."

- Reversal - "Are you going to be a mindless conformist drone drinking milk and water like everyone else, or will you wake up and drink my product?"[3]

Ambiguity effect

- People choose known wins over unknown wins is a cognitive bias where decision making is affected by a lack of information, or "ambiguity".[1] The effect implies that people tend to select options for which the probability of a favorable outcome is known, over an option for which the probability of a favorable outcome is unknown. The effect was first described by Daniel Ellsberg in 1961.[2]

Antiprocess

- the preemptive recognition and marginalization of undesired information by the interplay of mental defense mechanisms: the subconscious compromises information that would cause cognitive dissonance. It is often used to describe a difficulty encountered when people with sharply contrasting viewpoints are attempting (and failing) to discuss a topic.

- In other words, when one is debating with another, there may be a baffling disconnect despite one's apparent understanding of the argument. Despite the apparently sufficient understanding to formulate counter-arguments, the mind of the debater does not allow him to be swayed by that knowledge.

- The mind is capable of multitasking;

- The mind has the innate capability to evaluate and select information at a preconscious level so that we are not overwhelmed with the processing requirements;

- It is not feasible to maintain two contradictory beliefs at the same time;

- It is not possible for people to be aware of every factor leading up to decisions they make;

- People learn argumentatively effective but logically invalid defensive strategies (such as rhetorical fallacies);

- People tend to favour strategies of thinking that have served them well in the past; and

- The truth is just too unpalatable to the mind to accept.

Apophenia (/æpoʊˈfiːniə/)

- The tendency to mistakenly perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things

Attribution effect

- Humans are motivated to assign causes to their actions and behaviors.[1] In social psychology, attribution is the process by which individuals explain the causes of behavior and events. Models to explain this process are called attribution theory.[2] Psychological research into attribution began with the work of Fritz Heider in the early 20th century, and the theory was further advanced by Harold Kelley and Bernard Weiner.

Augustine’s laws

- Law Number XV: The last 10 percent of performance generates one-third of the cost and two-thirds of the problems.

- Law Number XXII: If stock market experts were so expert, they would be buying stock, not selling advice.

- Law Number XXIII: Any task can be completed in only one-third more time than is currently estimated.

- Law Number XXIV: The only thing more costly than stretching the schedule of an established project is accelerating it, which is itself the most costly action known to man.

- Law Number XXIX: Executives who do not produce successful results hold on to their jobs only about five years. Those who produce effective results hang on about half a decade.

- Law Number XXXVI: The thickness of the proposal required to win a multimillion dollar contract is about one millimeter per million dollars. If all the proposals conforming to this standard were piled on top of each other at the bottom of the Grand Canyon it would probably be a good idea.

- Law Number VI: A hungry dog hunts best. A hungrier dog hunts even better.

Ben Franklin effect

- a proposed psychological phenomenon: a person who has already performed a favor for another is more likely to do another favor for the other than if they had received a favor from that person

- In his autobiography, Franklin explains how he dealt with the animosity of a rival legislator when he served in the Pennsylvania legislature in the 18th century: Having heard that he had in his library a certain very scarce and curious book, I wrote a note to him, expressing my desire of perusing that book, and requesting he would do me the favour of lending it to me for a few days. He sent it immediately, and I return'd it in about a week with another note, expressing strongly my sense of the favour. When we next met in the House, he spoke to me (which he had never done before), and with great civility; and he ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.

Bleeding Edge

- Bleeding edge technology is a category of technologies so new that they could have a high risk of being unreliable and lead adopters to incur greater expense in order to make use of them.

Branolini’s Law (The Bullshit asymmetry principle)

- The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.

Brooks law

- an observation about software project management according to which "adding human resources to a late software project makes it later".[1][2] It was coined by Fred Brooks in his 1975 book The Mythical Man-Month. According to Brooks, there is an incremental person who, when added to a project, makes it take more, not less time. This is similar to the general law of diminishing returns in economics.

Bulverism

- A logical fallacy. The method of Bulverism is to "assume that your opponent is wrong, and explain his error." The Bulverist assumes a speaker's argument is invalid or false and then explains whythe speaker came to make that mistake, attacking the speaker or the speaker's motive. The term Bulverism was coined by C. S. Lewis[1] to poke fun at a very serious error in thinking that, he alleges, recurs often in a variety of religious, political, and philosophical debates.

- You must show that a man is wrong before you start explaining why he is wrong. The modern method is to assume without discussion that he is wrong and then distract his attention from this (the only real issue) by busily explaining how he became so silly.

Catfish Effect

- The catfish effect is the effect that a strong competitor has in causing the weak to better themselves.[1] Actions done to actively apply this effect (for example, by the human resource department) in an organization, are termed catfish management.[2]

- In Norway, live sardines are several times more expensive than frozen ones, and are valued for better texture and flavor. It was said that only one ship could bring live sardine home, and the shipmaster kept his method a secret. After he died, people found that there was one catfish in the tank. The catfish keeps swimming, and the sardines try to avoid this predator. This increased level of activity keeps the sardines active instead of becoming sedentary. (According to Vince from Catfish the Movie)[citation needed]

- In human resource management, this is a method used to motivate a team so that each member feels strong competition, thus keeping up the competitiveness of the whole team.

Checkhov's gun

- Every element in a story must be necessary, and irrelevant elements should be removed; elements should not appear to make "false promises" by never coming into play.

Chewbacca Defense

- In a jury trial, a Chewbacca defense is a legal strategy in which a criminal defense lawyer tries to confuse the jury rather than refute the case of the prosecutor. It is an intentional distraction or obfuscation.

Conjunction Fallacy

- The conjunction fallacy (also known as the Linda problem) is a formal fallacy that occurs when it is assumed that specific conditions are more probable than a single general one.

- Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

- Which is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Conway’s Law

- Conway's law is an adage named after computer programmer Melvin Conway, who introduced the idea in 1967.[1] It states that

- organizations which design systems ... are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

- Evidence in support of Conway's law has been published by a team of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard Business School researchers who, using "the mirroring hypothesis" as an equivalent term for Conway's law, found "strong evidence to support [the] mirroring hypothesis", and that "significant differences in [product] modularity" were "consistent with a view that distributed teams tend to develop more modular products".[8]

- Additional and likewise supportive case studies of Conway's law have been conducted by Nagappan, Murphy and Basili at the University of Maryland in collaboration with Microsoft,[9] and by Syeed and Hammouda at Tampere University of Technology in Finland.[10]

Chronological fallacy

- A thesis is deemed incorrect because it was commonly held when something else, known to be false, was also commonly held

Cognitive Dissonance

- is the mental discomfort (psychological stress) experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. This discomfort is triggered by a situation in which a person’s belief clashes with new evidence perceived by the person. When confronted with facts that contradict beliefs, ideals, and values, people will try to find a way to resolve the contradiction to reduce their discomfort.

Crab mentality

- Crab mentality, also known as crabs in a bucket (also barrel, basket, or pot) mentality, is a way of thinking best described by the phrase "if I can't have it, neither can you"

Cratylism

- holds that the fluid nature of ideas, words, and communications leaves them fundamentally baseless, and possibly unable to support logic and reason. It is distinguished from linguisticity by the problematic status of style - that in a natural language, where a perfect connection is found between word and things, variations of style are no longer conceivable.[2]

Courtier's reply

- a criticism is dismissed by claiming that the critic lacks sufficient knowledge, credentials, or training to credibly comment on the subject matter.

Cunningham's Law

- Ward is credited with the idea: "The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question, it's to post the wrong answer."[14] This refers to the observation that people are quicker to correct a wrong answer than to answer a question.

Campbell's law

- an adage developed by Donald T. Campbell, a psychologist and social scientist who often wrote about research methodology, which states:

- "The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor."[1]

Confused Deputy problem

- Tricking an authority to do bad things.

- When checking out at a grocery store, the cashier will scan the barcode of each item to determine the total cost. A thief could replace barcodes on his items with those of cheaper items. In this attack the cashier is a confused deputy that is using seemingly valid barcodes to determine the total cost.

Creeping normality

- Creeping normality or death by a thousand cuts[1] is the way a major change can be accepted as a normal situation if it happens slowly, through unnoticeable increments of change. The change could otherwise be regarded as objectionable if it took place in a single step or short period.

Definitional Retreat

- changing the meaning of a word to deal with an objection raised against the original wording.

Dunning–Kruger effect

- People think they are smarter than they really are.

Decoy Effect

- In marketing, the decoy effect (or attraction effect or asymmetric dominance effect) is the phenomenon whereby consumers will tend to have a specific change in preference between two options when also presented with a third option that is asymmetrically dominated.[1] An option is asymmetrically dominated when it is inferior in all respects to one option; but, in comparison to the other option, it is inferior in some respects and superior in others. In other words, in terms of specific attributes determining preferences, it is completely dominated by (i.e., inferior to) one option and only partially dominated by the other. When the asymmetrically dominated option is present, a higher percentage of consumers will prefer the dominating option than when the asymmetrically dominated option is absent. The asymmetrically dominated option is therefore a decoy serving to increase preference for the dominating option. The decoy effect is also an example of the violation of the independence of irrelevant alternatives axiom of decision theory.

Displacement activities

- occur when an animal experiences high motivation for two or more conflicting behaviours: the resulting displacement activity is usually unrelated to the competing motivations. Birds, for example, may peck at grass when uncertain whether to attack or flee from an opponent; similarly, a human may scratch their head when they do not know which of two options to choose. Displacement activities may also occur when animals are prevented from performing a single behaviour for which they are highly motivated. Displacement activities often involve actions which bring comfort to the animal such as scratching, preening, drinking or feeding.

Default Option effect

- Among the set of options that agents choose from, the default option is the option the chooser will obtain if he or she does nothing. Broader interpretations of default options include options that are normative or suggested. Experiments and observational studies show that making an option a default increases the likelihood that it is chosen; this is called the default effect. Different causes for this effect have been discussed. Setting or changing defaults therefore has been proposed as an effective way of influencing behavior—for example, with respect to deciding whether to become an organ donor,[1] giving consent to receive e-mail marketing, or choosing the level of one's retirement contributions.

Doctorow’s Law

- Anytime someone puts a lock on something you own, against your wishes, and doesn't give you the key, they're not doing it for your benefit.

Einstellung Effect

- The Einstellung effect is the negative effect of previous experience when solving new problems.

Endowment Effect

- In psychology and behavioral economics, the endowment effect (also known as divestiture aversion and related to the mere ownership effect in social psychology[1]) is the finding that people are more likely to retain an object they own than acquire that same object when they do not own it.

Embrace, Extend, extinguish

- "Embrace, extend, and extinguish",[1] (EEE) also known as "embrace, extend, and exterminate",[2] is a phrase that the U.S. Department of Justice found[3] was used internally by Microsoft[4] to describe its strategy for entering product categories involving widely used standards, extending those standards with proprietary capabilities, and then using those differences to strongly disadvantage its competitors.

Effort Justification

- An idea and paradigm in social psychology stemming from Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance.[1] Effort justification is a person's tendency to attribute a value to an outcome, which they had to put effort into achieving, greater than the objective value of the outcome.

Ethical Intuitionism

- Ethical intuitionism (also called moral intuitionism) is a family of views in moral epistemology (and, on some definitions, metaphysics). At minimum, ethical intuitionism is the thesis that our intuitive awareness of value, or intuitive knowledge of evaluative facts, forms the foundation of our ethical knowledge.

- I intuitively hate gays, therefore gays are bad.

- Related to ‘Moral Sense theory’ which says we can discover what is moral based on how we emotionally react to it.

Fallacy of division

- A fallacy of division is the error in logic that occurs when one reasons that something that is true for a whole must also be true of all or some of its parts.

An example:

- The 2nd grade in Jefferson elementary eats a lot of ice cream

- Carlos is a 2nd grader in Jefferson elementary

- Therefore, Carlos eats a lot of ice cream

False dilemma

- A type of informal fallacy in which something is falsely claimed to be an "either/or" situation, when in fact there is at least one additional option.

Form Follows function

- A thing should be designed in accordance to how it will be used.

Fox and the Grape

- One of the Aesop's fables,[1] numbered 15 in the Perry Index.[2] The narration is concise and subsequent retellings have often been equally so. The story concerns a fox that tries to eat grapes from a vine but cannot reach them. Rather than admit defeat, he states they are undesirable. The expression "sour grapes" originated from this fable.[3]

Fredkin's paradox

- concerns the negative correlation between the difference between two options and the difficulty of deciding between them. Developed further, the paradox constitutes a major challenge to the possibility of pure instrumental rationality.

- Proposed by Edward Fredkin, it reads: "The more equally attractive two alternatives seem, the harder it can be to choose between them—no matter that, to the same degree, the choice can only matter less."[1]Thus, a decision-making agent might spend the most time on the least important decisions.

Fundamental Attribution Error

- In social psychology, fundamental attribution error (FAE), also known as correspondence bias or attribution effect, is the concept that, in contrast to interpretations of their own behavior, people tend to (unduly) emphasize the agent's internal characteristics (character or intention), rather than external factors, in explaining other people's behavior. This effect has been described as "the tendency to believe that what people do reflects who they are".[1]

Gambler’s Fallacy

- The gambler's fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the mistaken belief that, if something happens more frequently than normal during a given period, it will happen less frequently in the future (or vice versa).

Gaslighting

- A form of psychological manipulation that seeks to sow seeds of doubt in a targeted individual or in members of a targeted group, making them question their own memory, perception, and sanity. Using persistent denial, misdirection, contradiction, and lying, it attempts to destabilize the victim and delegitimize the victim's belief.

Gish Gallop

- The Gish gallop is a technique used during debating that focuses on overwhelming an opponent with as many arguments as possible, without regard for accuracy or strength of the arguments.

Groupthink

- The psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative viewpoints by actively suppressing dissenting viewpoints, and by isolating themselves from outside influences.

To make groupthink testable, Irving Janis devised eight symptoms indicative of groupthink.

Type I: Overestimations of the group — its power and morality

- Illusions of invulnerability creating excessive optimism and encouraging risk taking.

- Unquestioned belief in the morality of the group, causing members to ignore the consequences of their actions.

Type II: Closed-mindedness

- Rationalizing warnings that might challenge the group's assumptions.

- Stereotyping those who are opposed to the group as weak, evil, biased, spiteful, impotent, or stupid.

Type III: Pressures toward uniformity

- Self-censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus.

- Illusions of unanimity among group members, silence is viewed as agreement.

- Direct pressure to conform placed on any member who questions the group, couched in terms of "disloyalty"

- Mindguards— self-appointed members who shield the group from dissenting information.

Cause of groupthink:

1. High group cohesiveness

Janis emphasized that cohesiveness is the main factor that leads to groupthink. Groups that lack cohesiveness can of course make bad decisions, but they do not experience groupthink. In a cohesive group, members avoid speaking out against decisions, avoid arguing with others, and work towards maintaining friendly relationships in the group. If cohesiveness gets to such a high level where there are no longer disagreements between members, then the group is ripe for groupthink.

- deindividuation: group cohesiveness becomes more important than individual freedom of expression

2. Structural faults

Cohesion is necessary for groupthink, but it becomes even more likely when the group is organized in ways that disrupt the communication of information, and when the group engages in carelessness while making decisions.

- insulation of the group: can promote the development of unique, inaccurate perspectives on issues the group is dealing with, and can then lead to faulty solutions to the problem.

- lack of impartial leadership: leaders can completely control the group discussion, by planning what will be discussed, only allowing certain questions to be asked, and asking for opinions of only certain people in the group. Closed style leadership is when leaders announce their opinions on the issue before the group discusses the issue together. Open style leadership is when leaders withhold their opinion until a later time in the discussion. Groups with a closed style leader have been found to be more biased in their judgments, especially when members had a high degree for certainty. Thus, it is best for leaders to take an open style leadership approach, so that the group can discuss the issue without any pressures from the leader.

- lack of norms requiring methodological procedures

- homogeneity of members' social backgrounds and ideology

3. Situational context:

- highly stressful external threats: High stake decisions can create tension and anxiety, and group members then may cope with the decisional stress in irrational ways. Group members may rationalize their decision by exaggerating the positive consequences and minimizing the possible negative consequences. In attempt to minimize the stressful situation, the group will make a quick decision with little to no discussion or disagreement about the decision. Studies have shown that groups under high stress are more likely to make errors, lose focus of the ultimate goal, and use procedures that members know have not been effective in the past.

- recent failures: can lead to low self-esteem, resulting in agreement with the group in fear of being seen as wrong.

- excessive difficulties on the decision-making task

- time pressures: group members are more concerned with efficiency and quick results, instead of quality and accuracy. Additionally, time pressures can lead to group members overlooking important information regarding the issue of discussion.

- moral dilemma

Preventing groupthink

- Leaders should assign each member the role of "critical evaluator". This allows each member to freely air objections and doubts.

- Leaders should not express an opinion when assigning a task to a group.

- Leaders should absent themselves from many of the group meetings to avoid excessively influencing the outcome.

- The organization should set up several independent groups, working on the same problem.

- All effective alternatives should be examined.

- Each member should discuss the group's ideas with trusted people outside of the group.

- The group should invite outside experts into meetings. Group members should be allowed to discuss with and question the outside experts.

- At least one group member should be assigned the role of Devil's advocate. This should be a different person for each meeting.

Gold Plating

- In time management, Gold plating is the phenomenon of working on a project or task past the point of diminishing returns. For example: after having met the requirements, the project manager or the developer works on further enhancing the product, thinking the customer will be delighted to see additional or more polished features, rather than what was asked for or expected. The customer might be disappointed in the results, and the extra effort by the developer might be futile.

Hitchens's razor

- an epistemological razor asserting that the burden of proof regarding the truthfulness of a claim lies with the one who makes the claim, and if this burden is not met, the claim is unfounded, and its opponents need not argue further in order to dismiss it.

Hanlon's razor

- never attribute to malice which is better explained by stupidity.

Hofstadter's law

- Hofstadter's law is a self-referential adage, coined by Douglas Hofstadter in his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1979) to describe the widely experienced difficulty of accurately estimating the time it will take to complete tasks of substantial complexity:[1][2]

- Hofstadter's Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law.

I’m entitled to my opinion

- I'm entitled to my opinion or I have a right to my opinion is a logical fallacy in which a person discredits any opposition by claiming that they are entitled to their opinion. The statement exemplifies a red herring or thought-terminating cliché. The logical fallacy is often presented as Let's agree to disagree. Whether one has a particular entitlement or right is irrelevant to whether one's assertion is true or false. To assert the existence of the right is a failure to assert any justification for the opinion. Such an assertion, however, can also be an assertion of one's own freedom or of a refusal to participate in the system of logic at hand.[1][2][3]

Ipse Dixit

- Ipse dixit (Latin for "he said it himself") is an assertion without proof; or a dogmatic expression of opinion.[1]

- The fallacy of defending a proposition by baldly asserting that it is "just how it is" distorts the argument by opting out of it entirely: the claimant declares an issue to be intrinsic, and not changeable.[2]

Inventor’s paradox

- The inventor's paradox is a phenomenon that occurs in seeking a solution to a given problem. Instead of solving a specific type of problem, which would seem intuitively easier, it can be easier to solve a more general problem, which covers the specifics of the sought-after solution. The inventor's paradox has been used to describe phenomena in mathematics, programming, and logic, as well as other areas that involve critical thinking.

Irrational escalation

- The phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the decision was probably wrong. Also known as the sunk cost fallacy.

IKEA effect

- A cognitive bias in which consumers place a disproportionately high value on products they partially created. The name derives from the name of Swedish manufacturer and furniture retailer IKEA, which sells many furniture products that require assembly.

Jevon’s Paradox

- In economics, the Jevons paradox (/ˈdʒɛvənz/; sometimes Jevons effect) occurs when technological progress or government policy increases the efficiency with which a resource is used (reducing the amount necessary for any one use), but the rate of consumption of that resource rises due to increasing demand.[1] The Jevons paradox is perhaps the most widely known paradox in environmental economics.[2] However, governments and environmentalists generally assume that efficiency gains will lower resource consumption, ignoring the possibility of the paradox arising.[3]

Kerkhoff’s principle

- "one ought to design systems under the assumption that the enemy will immediately gain full familiarity with them". Don’t try to hide things to make them safer. This is in contrast to ‘security through obscurity”

Keynesian Beauty Contest

- Keynes described the action of rational agents in a market using an analogy based on a fictional newspaper contest, in which entrants are asked to choose the six most attractive faces from a hundred photographs. Those who picked the most popular faces are then eligible for a prize.

- A naive strategy would be to choose the face that, in the opinion of the entrant, is the most handsome. A more sophisticated contest entrant, wishing to maximize the chances of winning a prize, would think about what the majority perception of attractive is, and then make a selection based on some inference from his knowledge of public perceptions. This can be carried one step further to take into account the fact that other entrants would each have their own opinion of what public perceptions are. Thus the strategy can be extended to the next order and the next and so on, at each level attempting to predict the eventual outcome of the process based on the reasoning of other rational agents.

- "It is not a case of choosing those [faces] that, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those that average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees." (Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936).

Law of Jante

- The Law of Jante (Danish: Janteloven)[note 1] is a code of conduct known in Nordic countries, that portrays doing things out of the ordinary, being overtly personally ambitious, or not conforming, as unworthy and inappropriate.

The ten rules state:

- You're not to think you are anything special.

- You're not to think you are as good as we are.

- You're not to think you are smarter than we are.

- You're not to imagine yourself better than we are.

- You're not to think you know more than we do.

- You're not to think you are more important than we are.

- You're not to think you are good at anything.

- You're not to laugh at us.

- You're not to think anyone cares about you.

- You're not to think you can teach us anything.

Law of the instrument

- An over-reliance on a familiar tool or methods, ignoring or under-valuing alternative approaches. "If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail."

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development

Loss Aversion

- In cognitive psychology and decision theory, loss aversion refers to people's tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains: it is better to not lose $5 than to find $5. The principle is very prominent in the domain of economics. What distinguishes loss aversion from risk aversion is that the utility of a monetary payoff depends on what was previously experienced or was expected to happen. Some studies have suggested that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains.[1]Loss aversion was first identified by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.[2]

Lindy effect

- a theory that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things like a technology or an idea is proportional to their current age, so that every additional period of survival implies a longer remaining life expectancy

Murphy's law

- Anything that could go wrong will go wrong

Newton's flaming laser sword

- "what cannot be settled by experiment is not worth debating".

McNamara Fallacy

- The first step is to measure whatever can be easily measured. This is OK as far as it goes. The second step is to disregard that which can't be easily measured or to give it an arbitrary quantitative value. This is artificial and misleading. The third step is to presume that what can't be measured easily really isn't important. This is blindness. The fourth step is to say that what can't be easily measured really doesn't exist. This is suicide.

Miller’s Law

- To understand what another person is saying, you must assume that it is true and try to imagine what it could be true of.

Moralistic Fallacy

- Warfare is destructive and tragic, and so it is not of human nature.

- Eating meat harms animals and the environment, and so no one has physiological use for it.

- Men and women ought to be given equal opportunities, and so women and men can do everything equally well.

- Unfaithfulness is immoral, and so it is unnatural to feel desire for others when in a monogamous relationship.

- The pill I am taking should have therapeutic effects on me, and so it does have therapeutic effects on me. (An instance of the placebo effect.)

Natrualistic Fallacy

- Warfare must be allowed because human violence is instinctive.

- Veganism is foolish because humans have eaten meat for thousands of years.

- Men and women should not have the same roles in society because men have more muscle mass and women can give birth.

- Adultery is acceptable because people can naturally want more sexual partners.

Occam's razor

- "simpler solutions are more likely to be correct than complex ones."

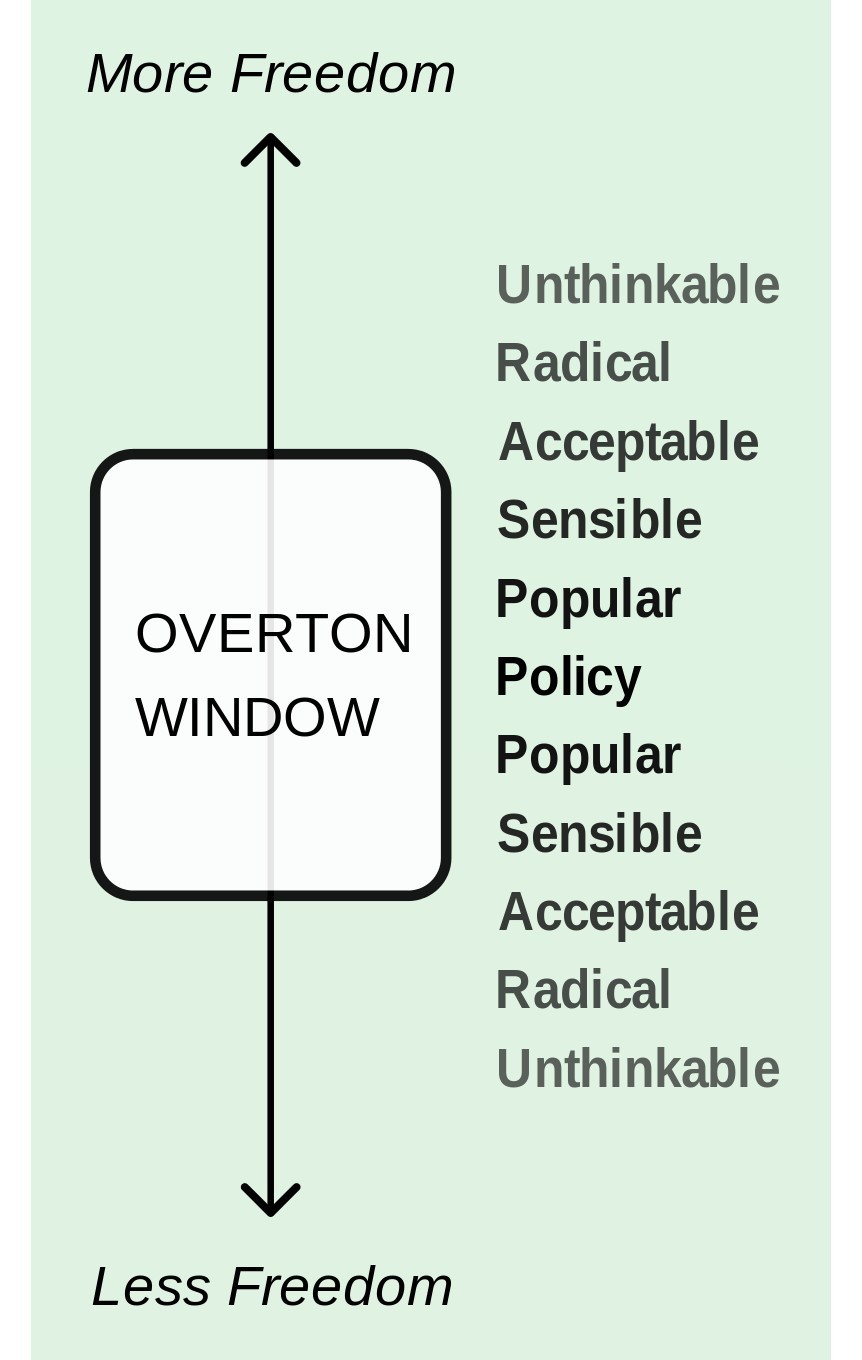

Overton Window

Peter principle

- a concept in management developed by Laurence J. Peter, which observes that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to their "level of incompetence". In other words, an employee is promoted based on their success in previous jobs until they reach a level at which they are no longer competent, as skills in one job do not necessarily translate to another.

Proof by Intimidation

- Proof by intimidation (or argumentum verbosum) is a jocular phrase used mainly in mathematics to refer to a style of presenting a purported mathematical proof by giving an argument loaded with jargon and appeal to obscure results, so that the audience is simply obliged to accept it, lest they have to admit their ignorance and lack of understanding

Propaganda Laundring

- Propaganda laundering is a method of using a less trusted or less popular platform to publish a story of dubious origin or veracity for the purposes of reporting on that report, rather than the story itself

Parkinson's law of triviality

- People argue about trivial things because they are easily understood

Path Dependence

- Path dependence explains how the set of decisions one faces for any given circumstance is limited by the decisions one has made in the past or by the events that one has experienced, even though past circumstances may no longer be relevant.[1]

Prevention paradox

- The prevention paradox was first formally described in 1981[1] by the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose. The prevention paradox describes the seemingly contradictory situation where the majority of cases of a disease come from a population at low or moderate risk of that disease, and only a minority of cases come from the high risk population (of the same disease). This is because the number of people at high risk is small.

Parkinson’s law

- Parkinson's law is the adage that "work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion". It is sometimes applied to the growth of bureaucracy in an organization.

Pluristic Ignorance

- In social psychology, pluralistic ignorance is a situation in which a majority of group members privately reject a norm, but go along with it because they incorrectly assume that most others accept it.[1] This is also described as "no one believes, but everyone thinks that everyone believes". In short, pluralistic ignorance is a bias about a social group, held by the members of that social group.[2][3]

Pareto principle (80/20 rule)

- 80% of effects from 20% of the causes

Pooh-pooh

- (also styled as poo-poo)[2] is a fallacy in informal logic that consists of dismissing an argument as being unworthy of serious consideration.[3] Scholars generally characterize the fallacy as a rhetorical device in which the speaker ridicules an argument without responding to the substance of the argument.[4]

Peak–end rule

- A psychological heuristic in which people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (i.e., its most intense point) and at its end, rather than based on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience. The effect occurs regardless of whether the experience is pleasant or unpleasant. According to the heuristic, other information aside from that of the peak and end of the experience is not lost, but it is not used.

Principle of Charity

- In philosophy and rhetoric, the principle of charity or charitable interpretation requires interpreting a speaker's statements in the most rational way possible and, in the case of any argument, considering its best, strongest possible interpretation.[1] In its narrowest sense, the goal of this methodological principle is to avoid attributing irrationality, logical fallacies, or falsehoods to the others' statements, when a coherent, rational interpretation of the statements is available. According to Simon Blackburn[2] "it constrains the interpreter to maximize the truth or rationality in the subject's sayings."

Premack’s Principle

- Premack's principle, or the relativity theory of reinforcement, states that more probable behaviors will reinforce less probable behaviors

- David Premack and his colleagues, and others, have conducted a number of experiments to test the effectiveness of the Premack principle in humans. One of the earliest studies was conducted with young children. Premack gave the children two response alternatives, eating candy or playing a pinball machine, and determined which of these behaviors was more probable for each child. Some of the children preferred one activity, some the other. In the second phase of the experiment, the children were tested with one of two procedures. In one procedure, eating was the reinforcing response, and playing pinball served as the instrumental response; that is, the children had to play pinball in order to eat candy. The results were consistent with the Premack principle: only the children who preferred eating candy over playing pinball showed a reinforcement effect. The roles of responses were reversed in the second test, with corresponding results. That is, only children who preferred playing pinball over eating candy showed a reinforcement effect. This study, among others, helps to confirm the Premack principle in showing that a high-probability activity can be an effective reinforcer for an activity that the subject is less likely to perform.(Domjan, 2010).

Putt's Law:

- "Technology is dominated by two types of people, those who understand what they do not manage and those who manage what they do not understand."[3]

Putt's Corollary

- "Every technical hierarchy, in time, develops a competence inversion." with incompetence being "flushed out of the lower levels" of a technocratic hierarchy, ensuring that technically competent people remain directly in charge of the actual technology while those without technical competence move into management.[3]

Principle of least effort

- a broad theory that covers diverse fields from evolutionary biology to webpage design. It postulates that animals, people, even well-designed machines will naturally choose the path of least resistance or "effort".

Principle of Least Astonishment (surprise)

- Do the thing that the person expects whenever possible. Only surprise when absolutely needed.

- Convention over configuration - Use ‘sensible’ defaults when making things. Try to leverage frameworks whenever possible

Principle of least privilege

- A thing, person should only have the resources, power that they need to do the thing that they do.

Pymgymalion effect

- The Pygmalion effect, or Rosenthal effect, is the phenomenon whereby others' expectations of a target person affect the target person's performance.[1] The effect is named after the Greek myth of Pygmalion, a sculptor who fell in love with a statue he had carved, or alternately, after the Rosenthal–Jacobson study (see below).

- A corollary of the Pygmalion effect is the golem effect, in which low expectations lead to a decrease in performance;[1]

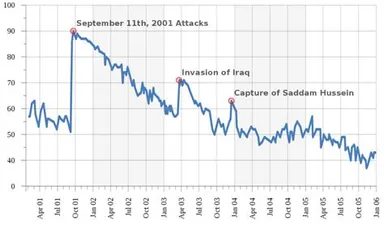

Rally ‘round the flag effect

- The rally 'round the flag effect (or syndrome) is a concept used in political science and international relations to explain increased short-run popular support of the President of the United States during periods of international crisis or war.[1] Because rally 'round The Flag effect can reduce criticism of governmental policies, it can be seen as a factor of diversionary foreign policy.[1]

Relativist Fallacy

- The relativist fallacy, also known as the subjectivist fallacy, is claiming that something is true for one person but not true for someone else. The fallacy is supposed to rest on the law of noncontradiction. The fallacy applies only to objective facts, or what are alleged to be objective facts, rather than to facts about personal tastes or subjective experiences, and only to facts regarded in the same sense and at the same time. On this formulation, the very name "relativist fallacy" begs the question against anyone who earnestly (however mistakenly or not) holds that there are no "objective facts." So some more work must be done, in a non-question-begging way, to make it clear wherein, exactly, the fallacy lies.

Rent-seeking

- a concept in public choice theory as well as in economics, that involves seeking to increase one's share of existing wealth without creating new wealth. Rent-seeking results in reduced economic efficiency through misallocation of resources, reduced wealth-creation, lost government revenue, heightened income inequality,[1] and potential national decline.

Risk compensation

- A theory which suggests that people typically adjust their behavior in response to the perceived level of risk, becoming more careful where they sense greater risk and less careful if they feel more protected. Although usually small in comparison to the fundamental benefits of safety interventions, it may result in a lower net benefit than expected.[n 1]

- By way of example, it has been observed that motorists drove faster when wearing seatbelts and closer to the vehicle in front when the vehicles were fitted with anti-lock brakes. There is also evidence that the risk compensation phenomenon could explain the failure of condom distribution programs to reverse HIV prevalence and that condoms may foster disinhibition, with people engaging in risky sex both with and without condoms.

Role Seduction

- Role suction is a term introduced in the United States by Fritz Redl in the mid-20th century to describe the power of a social group to allocate roles to its members. W. R. Bion's group dynamics further explored the ways whereby the group (unconsciously) allocates particular functions to particular individuals in order to have its covert emotional needs met

Rule of least power

- Use the least powerful thing you can. Don’t ‘overkill.’ Often the more powerful something is, the less flexible it is.

Second System Effect

- The second-system effect (also known as second-system syndrome) is the tendency of small, elegant, and successful systems, to be succeeded by over-engineered, bloated systems, due to inflated expectations and overconfidence.[1]

Snackwell effect

- Snackwell effect is a phenomenon that states that dieters will eat more low-calorie cookies, such as SnackWells, than they otherwise would for normal cookies.[1][2

Straw man

- A form of argument and an informal fallacy based on giving the impression of refuting an opponent's argument, while actually refuting an argument that was not presented by that opponent.[1] One who engages in this fallacy is said to be "attacking a straw man."

Streisand Effect

- The Streisand effect is a phenomenon whereby an attempt to hide, remove, or censor a piece of information has the unintended consequence of publicizing the information more widely, usually facilitated by the Internet.[1] It is an example of psychological reactance, wherein once people are aware that some information is being kept from them, their motivation to access and spread it is increased.[2]

Sayre’s Law

- Sayre's law states, in a formulation quoted by Charles Philip Issawi: "In any dispute the intensity of feeling is inversely proportional to the value of the issues at stake." By way of corollary, it adds: "That is why academic politics are so bitter."

Special Pleading

- Special pleading is an informal fallacy wherein one cites something as an exception to a general or universal principle (without justifying the special exception).[1][2][3][4][5] This is the application of a double standard.[6][7]

Sturgeon's law

- 90% of everything is crap

Stein’s Law

- Anything that cannot go on forever will stop.

Streetlight Effect

- The streetlight effect, or the drunkard's search principle, is a type of observational bias that occurs when people only search for something where it is easiest to look.[1][2][3][4] Both names refer to a well-known joke:

Satisficing

- In decision making, satisficing refers to the use of aspiration levels when choosing from different paths of action. By this account, decision-makers select the first option that meets a given need or select the option that seems to address most needs rather than the "optimal" solution.

- Example: A task is to sew a patch onto a pair of jeans. The best needle to do the threading is a 4 inch long needle with a 3 millimeter eye. This needle is hidden in a haystack along with 1,000 other needles varying in size from 1 inch to 6 inches. Satisficing claims that the first needle that can sew on the patch is the one that should be used. Spending time searching for that one specific needle in the haystack is a waste of energy and resources.

Self-licensing

- (aka noble cause corruption, moral self-licensing, moral licensing, licensing effect, moral credential effect) is a term used in social psychology and marketing to describe the subconscious phenomenon whereby increased confidence and security in one's self-image or self-concept tends to make that individual worry less about the consequences of subsequent immoral behavior and, therefore, more likely to make immoral choices and act immorally.[1][2][3][4][5][6] In simple terms, self-licensing occurs when people allow themselves to indulge after doing something positive first; for example, drinking a diet soda with a greasy hamburger and fries can lead one to subconsciously discount the negative attributes of the meal's high caloric and cholesterol content.[7]

Shirky Principle

- In April 2010, Kevin Kelly cited the phrase "Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution", and called it the "Shirky Principle", as the phrasing reminded him of the clarity of the Peter Principle.[22][23][24]

Shoshin

- Shoshin (初心) is a word from Zen Buddhism meaning "beginner's mind." It refers to having an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject, even when studying at an advanced level, just as a beginner would.

Survivorship Bias

- Survivorship bias or survival bias is the logical error of concentrating on the people or things that made it past some selection process and overlooking those that did not, typically because of their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions in several different ways. It is a form of selection bias.

Thought terminating Cliche

- A thought-terminating cliché (also known as a "semantic stop-signs," "thought-stoppers" or "cliché thinking") is a form of loaded language, commonly used to quell cognitive dissonance.[1][2][3][4][5][6]Depending on context in which a phrase (or cliché) is used, it may actually be valid and not constitute as thought-terminating, it does constitute as such when its application intends to dismiss dissent or justify fallacious logic.[7]

- "It is what it is." - Adds no value to any debate, its intent is to disengage. "Why is it so?"[2]

- "Lies of the devil." - Used as a response to any fact that threatens the integrity of an individual/group.[11]

- "Stop thinking so much." - A literal request to stop any debate.[12]

- “It’s all good.” - In the event that the situation is not in fact in a good state, yet you want people to stop analysing it, say this.[13]

- "Here we go again." - Implies that the topic has been debated about too frequently and is never going to reach a conclusion, so you may as well stop the debate.[14]

- "A chain is only as strong as its weakest link." - While this example is supposed to be taken figuratively, it might be used to imply that a team is no better than the least productive member of that team which is not true.[7]

- "It's not a religion; it is a relationship." - Intends to divert criticism, and is considered to be an assertion absent of any evidence or reasons that rely on ones confusion. "Tell me why it's not a religion. Tell me what a relationship is exactly."[7]

Tyranny of Speaking the Truth

- Under duress, a deceptive party will permit the truth to be said. Once the truth is out in the open, the situation is bracketed with shrugs and responsible parties say, "in an ideal world we could act on that, but we're already doing something else." This paradox neutralizes the truth. Once explicit, the truth proves itself not to be the idea being acted on. Naturally, actions supersede ideas. In this way, speaking the truth reveals it is less real than the way things are going, and it is therefore somewhat untrue.

- Example: "Cockroaches live in the house because it is dirty."

"I know the house has roaches. A clean house doesn't, but this isn't a clean house." *shrug* *hold breath past reeking trash can*

Tone Policing

- Tone policing (also tone trolling, tone argument and tone fallacy) is an ad hominem and antidebate appeal based on genetic fallacy. It attempts to detract from the validity of a statement by attacking the tone in which it was presented rather than the message itself.

Tu quoque "argument"

Follows the pattern:[2]

- Person A makes claim X.

- Person B asserts that A's actions or past claims are inconsistent with the truth of claim X.

- Therefore, X is false.

- An example would be:

Peter: "Bill is guilty of defrauding the government out of tax dollars."

Bill: "How can you say that when you yourself have 20 outstanding parking tickets?"

Ultracrepidarianism

- the habit of giving opinions and advice on matters outside of one's knowledge.

VUCA

- V = Volatility. The nature and dynamics of change, and the nature and speed of change forces and change catalysts.

- U = Uncertainty. The lack of predictability, the prospects for surprise, and the sense of awareness and understanding of issues and events.

- C = Complexity. The multiplex of forces, the confounding of issues, no cause-and-effect chain and confusion that surrounds organization.

- A = Ambiguity. The haziness of reality, the potential for misreads, and the mixed meanings of conditions; cause-and-effect confusion.

Vacuous truth

- a claim that is technically true but meaningless, in the form of claiming that no A in B has C, when there is no A in B. For example, claiming that no mobile phones in the room are on when there are no mobile phones in the room at all.

Wirdth’s law

- Wirth's law is an adage on computer performance which states that software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware is becoming faster.

Willpower Paradox

- The willpower paradox is the idea that people may do things better by focusing less directly on doing them, implying that the direct exertion of volition may not always be the most powerful way to accomplish a goal.

- One experiment compared the performance of two groups of people doing anagrams. One group thought about their impending anagram task; the other thought about whether or not they would perform anagrams. The second group performed better than those who knew for sure that they would be working on anagrams. The same researcher, Ibrahim Senay (at University of Illinois in Urbana), found similarly that repeatedly writing the question "Will I?" was more powerful than writing the traditional affirmation "I will".[2]

Weasel Word

- A weasel word, or anonymous authority, is an informal term for words and phrases such as "researchers believe" and "most people think" which make arguments appear specific or meaningful, even though these terms are at best ambiguous and vague. Using weasel words may allow the audience to later deny any specific meaning if the statement is challenged, because the statement was never specific in the first place. Weasel words can be a form of tergiversation, and may be used in advertising and political statements to mislead.

Worse is better

- Software that is limited, but simple to use, may be more appealing to the user and market than the reverse.

Zanshin

- Zanshin (Japanese: 残心) is a state of awareness, of relaxed alertness

Zen of python

- Beautiful is better than ugly.

- Explicit is better than implicit.

- Simple is better than complex.

- Complex is better than complicated.

- Flat is better than nested.

- Sparse is better than dense.

- Readability counts.

- Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

- Although practicality beats purity.

- Errors should never pass silently.

- Unless explicitly silenced.

- In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

- There should be one—and preferably only one—obvious way to do it.

- Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

- Now is better than never.

- Although never is often better than right now.

- If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

- If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

- Namespaces are one honking great idea—let's do more of those!

Zero-risk bias

- A tendency to prefer the complete elimination of a risk even when alternative options produce a greater reduction in risk (overall).[1] It often manifests in cases where decision makers address problems concerning health, safety, and the environment.[2] Its effect on decision making has been observed in surveys presenting hypothetical scenarios and certain real-world policies (e.g. war against terrorism as opposed to reducing the risk of traffic accidents or gun violence) have been interpreted as being influenced by it. Another example involves a decision to reduce risk in one manager's area at the expense of increased risk for the larger organization.[3]

Zero-sum thinking

- Also known as zero-sum bias, is a cognitive bias that describes when an individual thinks that one situation is like a zero-sum game, where one person's gain would be another's loss.[1][2][3][4] The term is derived from game theory. However, unlike the game theory concept, zero-sum thinking refers to a psychological construct—a person's subjective interpretation of a situation. Zero-sum thinking is captured by the saying "your gain is my loss" (or conversely, "your loss is my gain"). Rozycka-Tran et al. (2015) defined zero-sum thinking as:

Zugzwang

- (German for "compulsion to move", pronounced [ˈtsuːktsvaŋ]) is a situation found in chess and other games wherein one player is put at a disadvantage because they must make a move when they would prefer to pass and not move. The fact that the player is compelled to move means that their position will become significantly weaker. A player is said to be "in zugzwang" when any possible move will worsen their position.[1]

John Solly

Hi, I'm John, a Software Engineer with a decade of experience building, deploying, and maintaining cloud-native geospatial solutions. I currently serve as a senior software engineer at New Light Technologies (NLT), where I work on a variety of infrastructure and application development projects.

Throughout my career, I've built applications on platforms like Esri and Mapbox while also leveraging open-source GIS technologies such as OpenLayers, GeoServer, and GDAL. This blog is where I share useful articles with the GeoDev community. Check out my portfolio to see my latest work!

Comments